This has to be my alllll-time favorite teaching method. There’s just something about it that gets students engaged in conversation, and they always get super animated in teaching their peers and giving detailed examples.

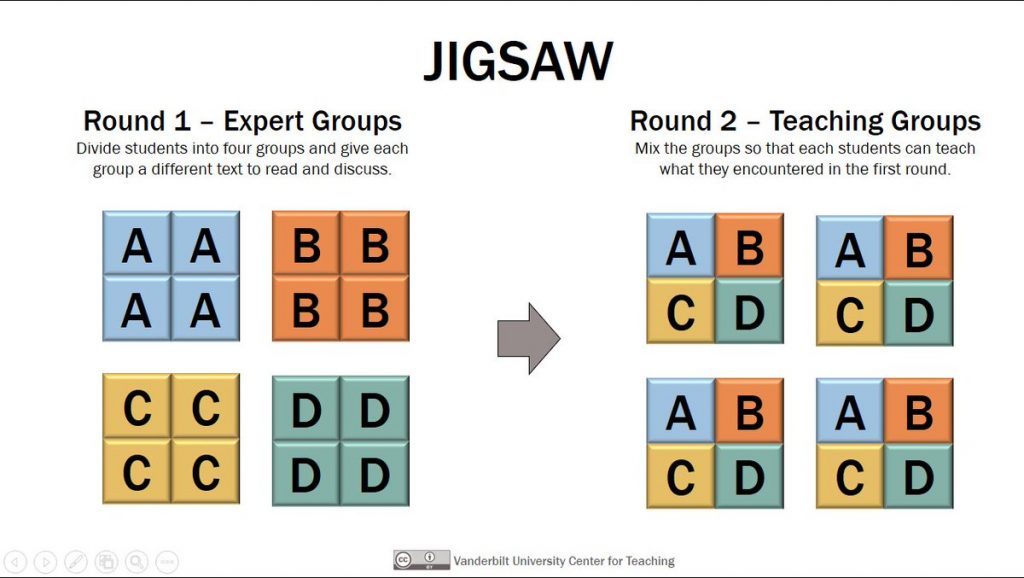

With this method, groups of students each read a different section / chapter. They group together in class first with those who read the same thing as them and unpack the reading, and then they’re divided up to teach their peers in groups. This can be modified in lots of ways (students can read / prep in class, etc.), but we’ll start with a basic approach.

The easiest way to explain is with an example.

First, one class period before I plan to do the jigsawing, I assign students to different groups of reading. One example of a book I love doing this with is Karl Jacoby’s Shadows at Dawn. The book is divided into sections that describe the experiences of different groups of Camp Grant Massacre participants (O’odham, Nnēē, Mexican, and American), and so I’d assign one group of students to read the chapters related to the O’Odham, one group to the Nnēē, etc., so that there’s an even distribution of students reading each set of chapters and four groups of students, each doing a different chunk of the reading.

In class, on the jigsaw day, first, students meet with all of the students who read the same reading – their “expert group.” So, all of the students who read the chapters about Mexican experience would discuss the chapters they read in common. I find it’s helpful to provide a set of questions to help focus their discussion. In this case, here are the questions I provided:

1) How does he tell the story of the Camp Grant Massacre from this group’s perspective? (Why does he tell the story in this way?)

2) How would you summarize the context he provides in this chapter that sets up this group’s participation in the Massacre? (4-5 main points)

3) In what ways is this group fractured? What different groups of these people disagree with each other, and what are they disagreeing about?

4) How does this group understand the violent acts that are being committed on their people and that they are committing on other peoples?

Even if students haven’t prepared well for class that day, they’re able to collectively share what they’ve read to develop solid answers to these questions, preparing anecdotes and details to share with their classmates in the next round. Sometimes I give students a handout that they can fill in these details for their group and for other groups, and sometimes I share a collective google doc, so that all students have access to the notes at the end, and can focus on active listening in the next stage.

Then, students break up into “jigsaw” groups – each group gets one piece of the puzzle. So, in this case, a second set of groups would be formed, with each group having one student who’s an expert in each the O’odham, Nnēē, Mexican, and American chapters. I give each student 5-6 minutes on a timer to teach their peers, and what I love most about this is students become storytellers, providing really rich details and anecdotes to their peers. With the expert group step, I’ve found even the students who have not read can still become competent enough to teach their peers the highlights of a reading. And even better, students deepened their comprehension by teaching it to others.

After this, we would typically have a discussion as a larger group, bringing together themes and bigger ideas that students have learned.

A few more benefits of this approach:

- It provides a way to tackle big pieces of scholarship without students needing to read an entire book.

- It is so much more engaging for students than me lecturing to the room. Students have to take a stake in the learning and get actively involved.

- While this may not work the first time you try it, students learn that they’ll be held accountable by their peers and so I’ve found students do try really hard to read for this activity.

How to Implement a Jigsaw:

- Choose a reading that lends itself to dividing up among students. It could be chapters of a book, sections of a chapter, or even complementary articles. Whatever you decide, the pieces should be able to stand alone. (For example, assigning sections of a novel wouldn’t work very well because each section likely requires knowing what happened in the previous sections. Assigning chapters of an edited collection, on the other hand, would work much better). If doing this with book chapters, I often assign the intro and conclusion to all students.

- Parcel these readings out to students. (I often make lists on the whiteboard and let students sign up as they participate in class during the prior session — functional and a motivator to participate!)

- In class, have students who read like readings discuss the reading together first in “expert groups.” It helps to give them some questions or guidelines as they work to frame the discussion. You could also have them take notes in a shared google doc together so the class can access their notes. At this stage it’s important that they all understand that they will each be teaching their peers about their material, and they ALL need to be familiar with their section.

- Divide students into jigsaw groups. Each group should have one person from each expert group – so if you assigned chapter 1, 2, 3, and 4, each group should have a representative from chapter 1, chapter 2, chapter 3, and chapter 4.

- Jigsaw group discussions. Again, setting guidelines and expectations is helpful here. I tell students each person should present for 5 minutes, and then I set a timer and give them a heads up when it’s time to switch. I also instruct students what they should do (e.g., provide their group’s answers to the 3 questions given and do so with detailed examples). Sometimes, I’ll allow students more than the allotted time if they really get into it.

- Big group discussion. Debrief at the end. This could try to cover group that these groups have already discussed and/or try to bring everything together to make larger conclusions, brainstorm takeaways, etc.

Often the first time doing this with a class will be challenging — some students certainly won’t prepare. Done several times over the course of a semester though, I’ve found students to rise to the occasion, once they know what to expect. I hope you give this awesome method a try!

Other Resources

- Lauren Horn Griffin, “Puzzling it Out: Teaching Marketable Skills in History Courses with the Jigsaw Technique,” (2015).

- Jigsaw Classroom, “Tips for Implementation.” An overview of student mindsets that might need to be considered when adopting the jigsaw method., written by Elliott Aronson who originally developed this technique.

- Jigsaw (teaching technique), on Wikipedia. Overview of some of the research that’s been done about this technique.

- Jennifer Gonzalez, “4 Things You Don’t Know About the Jigsaw Method,” Cult of Pedagogy (2015). This post details some of the socio-emotional benefits of this technique, as well as describing how it was created as an “antidote to racial tensions.”

I used to use these a lot. I should try the jigsaw method again.